Note: We were asked not to take photos in certain areas of the church without people in them. We were happy to comply. The pastor’s wife explained that they are discouraging photo piracy in this manner.

I cried. The power of The First African Union Baptist Church in Savannah, Georgia is overwhelming. In all of Savannah, the tour I took here continues to mean the most to me. In fact, I believe this particular tour impacted me more than any other that I’ve taken in the U.S. Why?

THE IMPORTANCE OF THIS CHURCH CANNOT BE OVER EMPHASIZED

This church has played a key role in the history of America’s religious and social evolution. The greats have spoken here. People such as John Cougar Mellencamp have petitioned the church for the honor of being baptized here.

You see, the First African Union Baptist Church is, in fact, the first African American church in North America. (note: two other churches claim the same honor (Silver Bluff Baptist Church in South Carolina dating from 1773 and the First Baptist Church of Petersburg, Virginia officially organized in 1774).

The rich history of this church begins before America was a country. That history continues through the American Revolution, the Civil War, the Underground Railroad, and the Civil Rights Movement still crucial today.

The First African Union Baptist Church was founded by and for slaves. Slaves paid for the church using the money they had saved to buy their freedom. Slaves built the church by hand in whatever time they could “get off” from plantation work. Slave women hauled bricks approximately 3 miles from the river to the building site.

HISTORY*

George Leile, a slave, was the first African American licensed by the Baptist Church to preach in Georgia. His charge was to preach to slaves on plantations along the Savannah River in Georgia and South Carolina. His master was a Baptist deacon who freed him before the American Revolution.

Leile first tried to establish a church in South Carolina but since it was illegal for slaves to gather together in worship, his attempt was unsuccessful. Upon reaching British-occupied Savannah, Leile built a congregation of black Baptists, slave and free, including David George and Andrew Bryan.

Leile built a congregation of about 30 people but wasn’t allowed to preach until 1775 by the British. He was granted his continued freedom by the British in exchange for his loyalty to the crown. When the British were defeated, Leile feared re-enslavement and fled to Jamaica to become the first Baptist missionary in 1788.

Before leaving for Jamaica, Leile ordained Andrew Bryan. Bryan was ordained in 1788 and his church was certified.

After meeting in a barn for years, Bryan oversaw the building of a wooden church and by 1800, the congregation had grown to about 700. Fifty of Bryan’s adult members could read, having been taught the Bible and three could write. The city’s first Black Sabbath school was established at First African Baptist and a school for Georgia’s black children was begun and run by Henry Francis, who had been ordained by Bryan.

There became a need for a larger, more permanent church building. The building you see today is that permanent church; its wooden walls now covered in stucco.

Reverend Bryan was beaten and discriminated against during his ministry. The current pastor cites writings that claim Bryan preached in a pool of his own blood and told his oppressors, he’d only stop sharing the gospel if they cut off his head. His owner came to the rescue. Historical papers belonging to the church state that, one time, “…landowners secretly witnessed their slaves praying at the church for a rich harvest and good health for their owners and responded positively.”

Bryan served at the church until 1812 when his nephew, Andrew Cox Marshall became the third pastor. Marshall had been a slave who drove a carriage. He is important for more than his service to the church. He rented himself out on his own time and became the first African American business owner. He negotiated his freedom by paying back the money he owed to his owner.

The stained glass windows above the altar are dazzling with their color and depict portraits of the original pastors of the church. The windows were installed during the pastorate of the 5th pastor. The current pastor is only the 17th.

PAID FOR, BUILT BY AND FOR SLAVES

The First African Union Baptist Church is the first house of worship in America built by slaves for slaves. Congregants chose to donate money they earned in their “spare time” to buy their freedom for the building of the church.

From 1855-1859, slave congregants worked, mostly by night, on the building. They worked by moonlight and bonfires. Even the bricks of the present day church building were made by slave labor. The famous “Savannah Grays” were highly-regarded local bricks made by artisan slaves on the nearby Hermitage Plantation.

Much of the interior remains original.

The pipe organ, baptismal pool and light fixtures are all original as well as the solid oak pews in the balcony, made by enslaved church members. The church walls are still painted “haint blue” to ward off spirits.

In the balcony, the slave hand-built pews have unusual designs on the ends. According to church history, they are messages of hope written in the native script of fugitive slaves. Historians and linguists are not sure about this theory. The pastor’s wife said some historians think the markings are a combination of Hebrew and various tribal languages.

THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD

In 1859, the same year First African Baptist Church construction was completed, an auction of 400 slaves took place in Savannah-one of the largest in U.S. history.

The First African Union Baptist Church was a central point in the Underground Railroad.

The red doors symbolically evoke a part of what the building meant to its congregants, the red color historically marked two things: “ownership and sanctuary.” The tour guide told us that the red doors symbolized a “safe place” for African Americans and slaves.

There are nine-patch quilt patterns in the ceiling of the church, which signify a safe haven.

A portion of the basement floor in the church has a 4-foot high space underneath where slaves hid until the cover of night at which time they were led through an underground tunnel leading to the river and boats to the north. A pattern of holes in the wooden floor cover the basement floor with those in certain portions of the floor serving as breathing holes for those hiding underneath.

The diamond shape of the holes dates back to an African prayer symbol called the BaKongo Cosmogram, which represents birth, life, death and rebirth.**(if interested, please see other interpretations of its meaning such as, “The Deep Meaning of the Kongo Cosmogram by Kiatezua Lubanzadio Luuyaluka, PhD. This article was first published on November 21, 2016 in the Journal of Black Studies.

The pastor’s wife also showed us an example of a freedom quilt. These quilts were hung on drying lines or in windows across the South with each block containing instructions for reaching freedom. Most slaves could not read but were told to interpret the quilt block “codes.” The quilt she showed us had a tree (“follow tree moss to the north”), a church (“go to the safe place”), a boat (“get in the boat”) and a bird flying (“fly to freedom”).

SEGREGATION

The First African Union Baptist Church served as a large meeting place in Savannah for white and blacks to meet during segregation. It is here where Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. first practiced his “I Have A Dream” speech.

Our tour took us to the basement documents room. This area houses the First African Union Baptist’s original church records, letters from political figureheads, Civil Rights photos, papers and other historical documents.

20TH AND 21ST CENTURY

The First African Baptist Church established the first federal credit union housed in a church in 1954. It continues to serve people today.

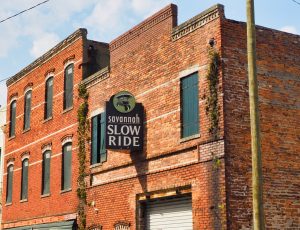

The church congregation has plans to purchase the brick building across the alley which was the building used to auction slaves in Savannah.

Tours of the church are only $10 and is a mere starting point to learn African American history in Savannah. Many African-American History and Points of Interest Tours are available in Savannah. DO NOT miss this national treasure when in Savannah. You will never forget the experience!

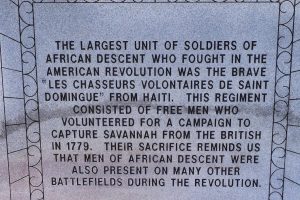

HAITIAN MEMORIAL IN FRANKLIN SQUARE

While waiting for your tour of the First African Union Baptist Church, spend some time examining the memorial in Franklin Square dedicated to the Haitians who served in the American Revolution.

Savannah is a fantastic place to learn more about African American history in America!!

First African Baptist Church

23 Montgomery Street

Savannah, Georgia 31401

https://www.firstafricanbc.com

TOURS:

Tuesday through Saturday: 11:00 a.m.; 2:00 p.m.; and 4:00 p.m.

Sundays: 1:00 p.m.

Ticket Pricing:

Adults: $10

Seniors: $9

Students & Military: $9

Children 5 and under are free

Contact: (912) 233-0636

*This narrative is a synthesis of information given during our tour, the church website (https://www.firstafricanbc.com) and texts in Wikipedia, GoSouth.com, www.edsmither.com and PBS Africans in America.

**”The Deep Meaning of the Kongo Cosmogram by Kiatezua Lubanzadio Luuyaluka, PhD. This article was first published on November 21, 2016 in the Journal of Black Studies.